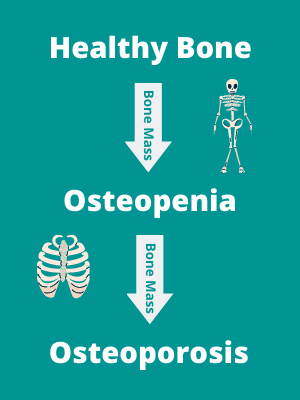

Our bones naturally become weaker as we age. Their structure, composition and function decline as bone mass decreases and changes occur in the microarchitecture. If you have a lower than average bone density, this is known as osteopenia. Osteopenia is common in people over the age of 50, but not everybody will develop the condition: genetics and lifestyle factors play a big role.

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder characterised by low bone mineral density, with an increased fracture risk. It is known as a ‘silent disease’, because the bone loss occurs without symptoms and often isn’t known about or investigated until a fracture occurs.

What we’ll cover:

What’s the difference between osteopenia and osteoporosis?

Osteopenia and osteoporosis can be thought of as certain points along the scale of bone mass loss. The difference between them is a measured loss of bone mineral density beyond a certain threshold. Osteopenia is considered the mid-way point between healthy bone mass and osteoporosis. Osteopenia is a significant risk factor for the development of osteoporosis, but the progression is not inevitable.

The increased fracture risk with osteoporosis has huge individual and societal costs. Fractures caused by osteoporosis most often occur in the spine, but are also common in the hip, wrist and forearm. As well as long-term pain, osteoporosis is associated with significant morbidity, loss of function, reduced quality of life and even mortality.

Osteoporosis is becoming increasingly more common. According to the NHS it affects over 3 million people in the UK and over half a million people every year are treated in hospital for fragility fractures. The risk increases significantly with age, and is more common in women (with a 4x increased risk) due to a number of factors.

While genetics are a factor, it is not all out of our control. Making certain lifestyle changes can help you to reduce your risk of developing osteopenia or osteoporosis, or manage the condition if it has already been diagnosed. We’ll explore these in more detail below.

What causes the loss of bone density?

Bones are constantly remodelling. This is controlled by a careful balance between cells called osteoclasts, which remove old bone, and the deposition of new bone by osteoblasts. A range of genetic and external lifestyle factors can affect this process. For example mechanical loading of bone, through weight bearing and resistance exercise (strength training), tips the balance in favour of osteoblasts leading to new bone formation in the areas exposed to load.

A steady balance is maintained until we reach our peak bone mass, which is roughly aged 20 in women, and 30 in men. After this peak mass is reached, the balance starts to tip in favour of osteoclast activity, with a slow gradual loss of bone density over time.

Sex hormones play an important role in bone remodelling throughout the lifetime. The hormone oestrogen affects a number of processes inhibiting osteoclast activity. This is one of the main factors causing the rapid loss of bone mass in women at menopause, and explains why women are at a much higher risk of developing osteoporosis. This rapid bone mass loss lasts for up to 10 years after menopause.

In men, testosterone is an important protector of bone mass, explaining their reduced risk of osteoporosis. However oestrogen also contributes to the age-related loss of bone mass in men, and studies have shown it is this reduction in oestrogen levels in men that is better associated with bone loss than testosterone. 1

So what are the risk factors for developing osteopenia and osteoporosis? And what can you do to prevent, or manage it?

Ways to prevent osteopenia and osteoporosis

Weight

A low body mass index is known to be correlated with reduced bone density, predisposing to osteoporosis. Equally on the other end of the scale, a high percentage of body fat, especially abdominal adiposity, has a strong association with low bone mineral density.

There is growing evidence of associations between bone mineral density and a number of metabolic abnormalities and cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, hyperglycaemia, central obesity and high blood lipids.2 Ultimately the best way to protect yourself is to maintain a healthy weight.

Smoking and alcohol

Smoking has an inverse relationship to bone mineral density. This is thought to be related to a number of factors including negatively impacting bone turnover, earlier menopause, lower body weight and breakdown of oestrogen.3 Chronic alcohol consumption is also linked to poor bone health and an increased risk of fractures. Alcohol interferes with calcium and the production of hormones related to bone health.4

Nutrition

There is strong evidence supporting calcium and vitamin D intake with bone mineral density. Calcium is an essential component of bones and is required for bone deposition. The majority (99%) of calcium is stored in the bones and teeth, with the remainder in the plasma, as it has a few other important roles in the body such as for cardiac function, blood coagulation and neuromuscular functioning.

If plasma levels drop, bone resorption (bone mass loss) occurs to maintain plasma levels. Adequate and regular intake of calcium is therefore required to maintain this balance. Absorption of calcium requires vitamin D in the small intestines.5

The best way to ensure adequate calcium is through the diet, from dairy products such as milk, cheese, yoghurt, fortified foods and some green vegetables. Supplementation is required if you are not able to meet the requirements through diet. Vitamin D is best obtained through exposure to sunlight, and is in very few foods.

Most of us do not absorb enough through sunlight, and supplement is required, at least for the wintery half of the year. The National Osteoporosis Foundation website provides more information on the recommended daily amounts of calcium and vitamin D for people of different ages.

Hormonal disorders, steroids and malabsorption disorders

A number of hormonal disorders can greatly increase the risk of osteoporosis such as hypogonadism, hyperparathyroidism, Cushing’s syndrome and early hysterectomy. Premature menopause, before the age of 45, has a strong association with bone loss and increased fracture risk.6

Long term use of oral steroid tablets, for conditions such as inflammatory arthritis, affects the amount of calcium absorbed and increases the calcium excretion. Diseases related to malabsorption are known risk factors for poor bone health, including Crohn’s disease and coeliac disease. Medications used to treat certain types of cancer, including breast and prostate, also affect hormone levels and can therefore impact bone density.7

There is also a known genetic link with osteoporosis. Having a parent with osteoporosis diagnosed, or who has suffered a fragility fracture greatly increases the risk of osteoporosis and fractures. While genetics are beyond our control, it’s important to be aware of the link between these and bone health, especially regarding the increased risk of osteoporosis. This might mean you need to be more careful with other factors that you can control, such as your diet and physical activity to manage this risk.

Physical activity and exercise

Low physical activity levels, particularly prolonged periods of bed rest, have been well evidenced to reduce bone mineral density. Bones thrive on physical loading and mechanical stress in order to tip the balance of bone remodelling in favour of deposition of new bone. The key is for the exercises to be weight bearing – meaning the bones are taking the load of the body weight, or more.

Weight bearing and resistance exercise in younger age is protective against osteoporosis, as it increases the peak bone mineral density, meaning any losses later in life have a reduced impact.8

Learn more: The Ultimate Guide to Strength Training For Older Adults

Traditionally, recommendations for exercise for older adults with low bone mineral density were weight bearing exercises of a low-load intensity, such as walking or Tai Chi. However recent evidence has challenged this. In order to effectively stimulate bone remodelling and osteogenesis, bone tissue must be exposed to mechanical load that exceeds that which is experienced during normal daily activities.

Aerobic exercises such as walking, cycling or swimming do not provide adequate stimulus for bones. Therefore higher intensity impact activities such as hopping and jumping, and progressive resistance training are now recommended to improve bone density. Both of which have been shown to be safe and effective, even in osteoporotic populations.9

The best evidence for the improvement of bone mineral density has come from studies which have used programmes of progressive resistance exercise working with a high mechanical load, performed at least twice weekly. These included exercises which worked the large muscles of the hip and spine.

High intensity weight bearing aerobic activity is also recommended, including: hopping, jumping, skipping, running and high-impact aerobics. High quality evidence has been published supporting the use of these in post-menopausal women and older men to improve bone density. Therefore current recommendations are to include both of these in a regular programme of exercise.

Although there is strong evidence supporting high impact and resistance exercise for increasing bone density, some remain anxious to recommend it for populations with low bone density due to a potential perceived risk of fracture. However, a recent randomised controlled trial has challenged this perception. The LIFTMOR Trial compared high-intensity resistance and impact training (HiRIT) with a low intensity home based intervention (control) in post-menopausal women with osteopenia and osteoporosis.10

Participants were randomised to the groups for 8 months of twice weekly sessions. The supervised HiRIT group performed 5 sets of 5 repetitions of exercises such as squats, deadlifts and overhead shoulder press, at loads of 80-85% of their 1 repetition maximum (the max weight/load they were able to lift or perform the exercise with). Jump chin-ups with a drop landing were also used for high intensity impact loading.

The low intensity home based group performed exercises similar to the traditional recommendations for osteoporosis patients, such as walking, stretching and low intensity body weight exercise such as lunges, calf raises and upper body exercises. After 8 months, a variety of measurements were taken with extremely positive results.

The women in the HiRIT group experienced significant increases in bone mineral density in the lumbar spine and the femoral neck (sites typically displaying low bone mineral density and at high risk of fracture). There were also increases in leg and back strength and functional performance measures. Crucially during the trial, no fractures or adverse events were observed.

Trials like this are vital to combat misconceptions, and to highlight the safety and effectiveness of this type of exercise for this population. However, it is important to caveat this trial was performed under supervision, and the authors have recommended that the protocol isn’t used in an unsupervised environment with this population. More evidence is now needed around unsupervised high intensity resistance programmes for this population.

In Summary

To conclude, we have a number of factors in our control to affect our bone health: including lifestyle factors, diet and physical activity. It is much easier to start these healthy habits early, and prevent the development of osteopenia or osteoporosis through a lifetime of habits ensuring healthy bones.

However, even in later years with the loss of bone mass (osteopenia) and with an osteoporosis diagnosis, evidence shows us that we can still take steps to maintain and even improve our bone mass.

Learn more: The Ultimate Guide to Strength Training For Older Adults

References

- Demontiero, O., Vidal, C., & Duque, G. (2012). Aging and bone loss: new insights for the clinician. Therapeutic advances in musculoskeletal disease, 4(2), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1759720X11430858

- Chen YY, Fang WH, Wang CC, Kao TW, Chang YW, et al. (2018) Body fat has stronger associations with bone mass density than body mass index in metabolically healthy obesity. PLOS ONE 13(11): e0206812. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0206812

- Christodoulou, C., & Cooper, C. (2003). What is osteoporosis?. Postgraduate medical journal, 79(929), 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1136/pmj.79.929.133

- Smoking and bone health. (n.d.). Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https://www.bones.nih.gov/health-info/bone/osteoporosis/conditions-behaviors/bone-smoking

- Sunyecz J. A. (2008). The use of calcium and vitamin D in the management of osteoporosis. Therapeutics and clinical risk management, 4(4), 827–836. https://doi.org/10.2147/tcrm.s3552

- Osteoporosis – Causes – NHS. (n.d.). Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/osteoporosis/causes/

- Osteoporosis – Causes – NHS. (n.d.). Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/osteoporosis/causes/

- Osteoporosis. (n.d.). Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https://www.versusarthritis.org/about-arthritis/conditions/osteoporosis/

- Hong, A. R., & Kim, S. W. (2018). Effects of Resistance Exercise on Bone Health. Endocrinology and metabolism (Seoul, Korea), 33(4), 435–444. https://doi.org/10.3803/EnM.2018.33.4.435

- Watson, S. L., Weeks, B. K., Weis, L. J., Harding, A. T., Horan, S. A., & Beck, B. R. (2018). High-Intensity Resistance and Impact Training Improves Bone Mineral Density and Physical Function in Postmenopausal Women With Osteopenia and Osteoporosis: The LIFTMOR Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, 33(2), 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3284