What we’ll cover:

What is osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis is a multifactorial disease of the joints. It is the most common joint disease, and the leading cause of pain and disability in adults. Studies estimate that it affects more than a quarter of the adult population. It commonly occurs in the knees and hips, and smaller joints of the hands and feet.

The classic features are gradually worsening pain and stiffness within these joints. Most of the time it doesn’t have an obvious cause. Although, there are a number of well accepted risk factors: increasing age, female sex, obesity, prior injury to the joint, prior repetitive over-use of the joint, low bone density, muscle weakness, joint laxity, as well as some genetic factors.

The Pathophysiology of Osteoarthritis

(Warning – some sciencey stuff coming up..)

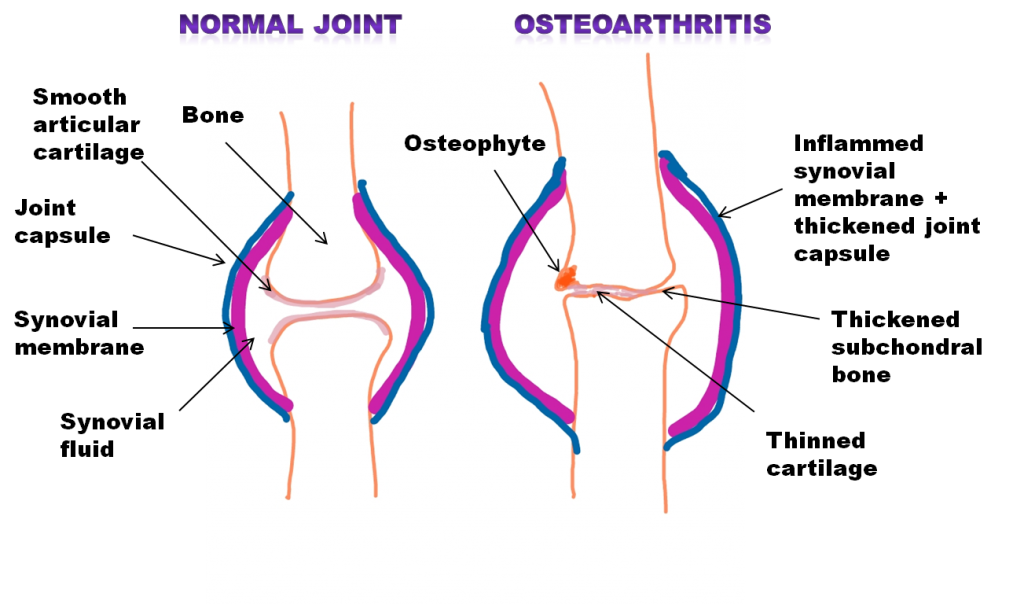

Osteoarthritis is primarily a condition of progressive loss of articular cartilage. This is the smooth connective tissue that covers the ends of two bones when they come together to form a joint. Various other changes are seen affecting the whole joint organ: thickening of the subchrondral bone (layer of bone just below the cartilage), osteophytes (small little bits of bone growth), inflammation of the synovium (the soft tissue lining the inner surface of the joint) and various levels of degeneration of ligaments (connective tissue structures responsible for joint stability) and menisci (cushioney cartilage which help shock absorption within the knee joints).

Despite the commonly held belief that osteoarthritis is a ‘wear and tear’ condition caused by excessive use of our joints, recent research is showing it is much more complicated than that.

Our joints usually do a really great job of maintaining their own health. There are lots of different helpful chemicals and proteins produced by the synovium (lining) on our joints, which keep our joint cartilage healthy. Unfortunately in osteoarthritis something causes a switch in the production of these proteins and chemicals to harmful ones. Inflammatory cells within the synovium are then ‘switched on’, adding to these harmful chemicals.

These harmful chemicals and proteins start to weaken the articular cartilage. Without a smooth articular joint surface, remodelling and changes within the subchondral bone develop, osteophytes are formed and inflammation occurs within the synovium. Over time the normal space within the joints is lost, known as joint space narrowing. All of these changes lead to the cardinal signs of pain, inflammation, swelling and stiffness.

There is also increasing evidence that the changes to the subchondral bone and the inflammation of the synovium can initiate and even lead to the progression of the disease.

Systemic chronic low-grade inflammation has also been found to contribute to the development and progression of the disease.

(Sciencey bit over)

So what causes osteoarthritis?

It all sounds very complex so far, and that’s because it is. Put simply, science doesn’t yet fully understand what causes all the cellular changes in osteoarthritis. But there is a general consensus moving away from considering osteoarthritis a condition purely caused by excessive overuse of a joint.

To make things even more complicated, there can be a substantial mismatch between disease severity and the symptoms of pain and stiffness. On scans people can show quite significant osteoarthritic joint changes, but have no pain. Alternatively, people can have quite severe pain and symptoms, but have scans which shown only minor joint changes.

Now this isn’t saying that there is no correlation between the experience of pain and stiffness and the joint changes. Of course there is, these are the most common symptoms of the disease. But it does tell us that it is not quite as simple as the symptoms involved being directly related to the progression of the disease. The pain experience itself is much more complex than that.

To summarise, what we are starting to understand is:

- Osteoarthritis is not simply a ‘wear and tear’ disease caused by excessive joint overuse

- Osteoarthritis is very common, although the cause is usually unknown

- Risk factors include increasing age, female gender, being overweight, previous joint injury, excessive joint use, genetics, low bone mass and low muscle mass.

- Increasing evidence shows changes at a cellular level cause a switch to the production of harmful chemicals and proteins which break down cartilage

- Lots of changes occur within different structures of the joint

- Inflammation and bone remodelling plays a bigger role in disease onset and progression than previously thought

- The structural changes within the joints don’t always directly relate to the pain and symptoms experience

Why exercise is the best treatment for osteoarthritis

Previously, with the accepted idea that osteoarthritis was caused by ‘wear and tear’, people tended to avoid using their painful arthritic joints to protect them. This led to people avoiding exercise and becoming fearful of movement. But new research actually shows that we should be doing the opposite.

Exercise, in the form of a combination of muscle strengthening and aerobic exercise, should be the first line of treatment for people with hip and knee osteoarthritis. High quality evidence supports its use in improving pain, physical functioning and quality of life. Exercise not only has a symptom-modifying effect in osteoarthritis, it also has a disease-modifying effect.

Strength training specifically has a vital role to play in the management and treatment of osteoarthritis. Stronger muscles means more protected joints, improved joint bio-mechanics and reductions in pain.

If you would like to learn more about the role of resistance training in treatment, read our next article covering 10 reasons why strength training is beneficial in osteoarthritis.